La vida en el último período de invernadero del planeta, el Eoceno. Jay Matternes / Museo Smithsonian, CC BY

La vida en el último período de invernadero del planeta, el Eoceno. Jay Matternes / Museo Smithsonian, CC BY

Las concentraciones de dióxido de carbono van hacia valores que no se habían visto en los últimos 200m años. El sol también se ha ido fortaleciendo gradualmente con el tiempo. Juntos, estos hechos significan que el clima puede estar encaminándose hacia una calidez no vista en los últimos 500 millones de años. ![]()

A lot has happened on Earth since 500,000,000BC – continents, oceans and mountain ranges have come and gone, and complex life has evolved and moved from the oceans onto the land and into the air. Most of these changes occur on very long timescales of millions of years or more. However, over the past 150 years global temperatures have increased by about 1?, ice caps and glaciers have retreated, polar sea-ice has melted, and sea levels have risen.

Algunos señalarán que el clima de la Tierra tiene sufrido cambios similares antes. ¿Así que cuál es el problema?

Los científicos pueden tratar de comprender climas pasados observando la evidencia encerrada en rocas, sedimentos y fósiles. Lo que esto nos dice es que sí, el clima ha cambiado en el pasado, pero la velocidad actual del cambio es muy inusual. Por ejemplo, el dióxido de carbono no se ha agregado a la atmósfera tan rápidamente como hoy por lo menos durante el pasado 66m años.

In fact, if we continue on our current path and exploit all convention fossil fuels, then as well as the rate of CO? emissions, the absolute climate warming is also likely to be unprecedented in at least the past 420m years. That’s according to a new study we have published in Nature Communications.

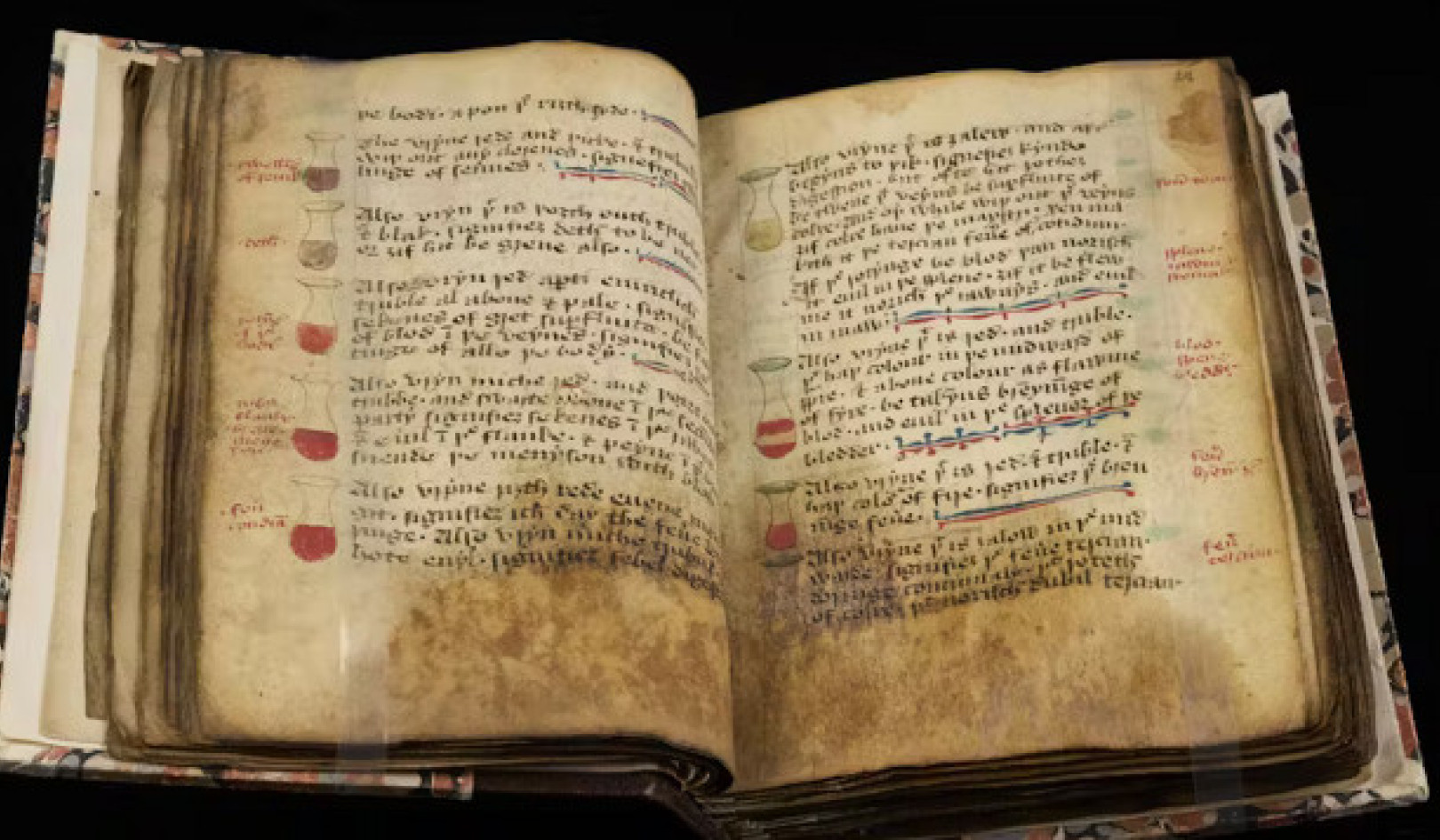

In terms of geological time, 1? of global warming isn’t particularly unusual. For much of its history the planet was significantly warmer than today, and in fact more often than not Earth was in what is termed a “greenhouse” climate state. During the last greenhouse state 50m years ago, global average temperatures were 10-15? warmer than today, the polar regions were ice-free, palmeras crecieron en la costa de la Antártida, y cocodrilos y tortugas se revolcaban en bosques pantanosos en lo que ahora es el Ártico congelado de Canadá.

En contraste, a pesar de nuestro calentamiento actual, todavía estamos técnicamente en un estado climático de "cámara de hielo", lo que simplemente significa que hay hielo en ambos polos. La Tierra ha hecho un ciclo natural entre estos dos estados climáticos cada 300m años más o menos.

Just prior to the industrial revolution, for every million molecules in the atmosphere, about 280 of them were CO? molecules (280 parts-per-million, or ppm). Today, due primarily to the burning of fossil fuels, concentrations are about 400 ppm. In the absence of any efforts to curtail our emissions, burning of conventional fossil fuels will cause CO? concentrations to be around 2,000ppm by the year 2250.

This is of course a lot of CO?, but the geological record tells us that the Earth has experienced similar concentrations several times in the past. For instance, our new compilation of data shows that during the Triassic, around 200m years ago, when dinosaurs first evolved, Earth had a greenhouse climate state with atmospheric CO? around 2,000-3,000ppm.

Por lo tanto, altas concentraciones de dióxido de carbono no necesariamente hacen que el mundo sea totalmente inhabitable. Los dinosaurios prosperaron, después de todo.

Eso no significa que esto no sea gran cosa, sin embargo. Para empezar, no hay duda de que la humanidad se enfrentará a importantes desafíos socioeconómicos relacionados con la cambio climático dramático y rápido eso resultará del rápido aumento a 2,000 o más ppm.

But our new study also shows that the same carbon concentrations will cause more warming in future than in previous periods of high carbon dioxide. This is because the Earth’s temperature does not just depend on the level of CO? (or other greenhouse gases) in the atmosphere. All our energy ultimately comes from the sun, and due to the way the sun generates energy through nuclear fusion of hydrogen into helium, its brightness has increased over time. Four and a half billion years ago when the Earth was young the sun was around 30% less bright.

So what really matters is the combined effect of the sun’s changing strength and the varying greenhouse effect. Looking through geological history we generally found that as the sun became stronger through time, atmospheric CO? gradually decreased, so both changes cancelled each other out on average.

Pero, ¿qué pasa en el futuro? No encontramos un período pasado cuando los impulsores del clima, o clima forzando, fue tan alto como lo será en el futuro si quemamos todo el combustible fósil fácilmente disponible. No se ha registrado nada parecido en el registro de rock durante al menos 420m años.

Un pilar central de la ciencia geológica es el principio uniformitarian: that “the present is the key to the past”. If we carry on burning fossil fuels as we are at present, by 2250 this old adage is sadly no longer likely to be true. It is doubtful that this high-CO? future will have a counterpart, even in the vastness of the geological record.

Acerca de los Autores

Gavin Foster, profesor de geoquímica de isótopos, Universidad de Southampton; Dana Royer, profesora de Ciencias de la Tierra y del Medio Ambiente, Wesleyan University, y Dan Lunt, profesor de Ciencia del Clima, Universidad de Bristol

Este artículo se publicó originalmente el La conversación. Leer el articulo original.

Libros relacionados

at InnerSelf Market y Amazon